Pear Rootstock – Pros and Cons by Tim Hamilton

From the Grapevine Winter (December) 2021

Years ago, after meeting Jim Ozzello, I became really interested in pears. Jim had as many as 21 pear varieties planted against his house as spire-type espaliers. He grafted all of his trees on quince rootstock. They were neatly planted on 2-foot centers and pruned close to the trunk to avoid overlap. The trees all produced fruit. Jim’s property was less than a mile from Lake Michigan which I believe put his orchard in a favorable micro-climate. Sooo I thought, easy peasy, I would do the same.

I successfully grafted a dozen trees on quince C and planted them in the ground where they thrived all summer. During the harsh winter, the grafts died although the rootstocks survived. I tried again, this time on the OHxF-333 rootstock, guessing that graft compatibility might be better and selecting OHxF-333 over OHxF-87 because it ought to produce a smaller tree. NINE years later…there were still no blossoms. I had also tried to stress the trees using aggressive branch bending with no success. While waiting for these trees to bloom, I had also purchased several pear trees on OHxF-87. All of those trees had blossomed and set fruit spurs.

I then contacted Dr. Stefano Musacchi, a professor in the Department of Horticulture at Washington State University, for his help with this problem. Dr. Musacchi replied that “the rootstock you selected, OHxF-333, has been abandoned for commercial use due to the reason that you mention. Low crop level. Probably it will be better to use OHxF-87, it is more vigorous but also more productive.”

I also checked out a few of the better suppliers in the industry. They all, with the exception of Grampa’s Orchard, only offer pear trees on OHxF-87.

So here are my take-aways on selecting pear rootstock:

OHxF-87 – My choice going forward. Can be used for both European and Asian pears. Best vigor and production. The height needs to be managed by pruning.

OHxF-333 – I will no longer use it.

Quince – In the past, 2 types have been offered by the club: quince C and quince A. There are two issues with quince. First, not all European pears are compatible and may require an interstem. Second, the graft unions may not be cold hardy. However, if you are close to the lake or farther south (I am located near the Illinois-Wisconsin border) it may still be an option.

Other recommendations:

–Check out Dr. Musacchi’s videos on YouTube. They are really good and science based.

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=BMAccZ604Os

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=oL2l004bLhc

–Pear tree limbs should be spread to 45 degrees from vertical as opposed to 90 degrees for apples.

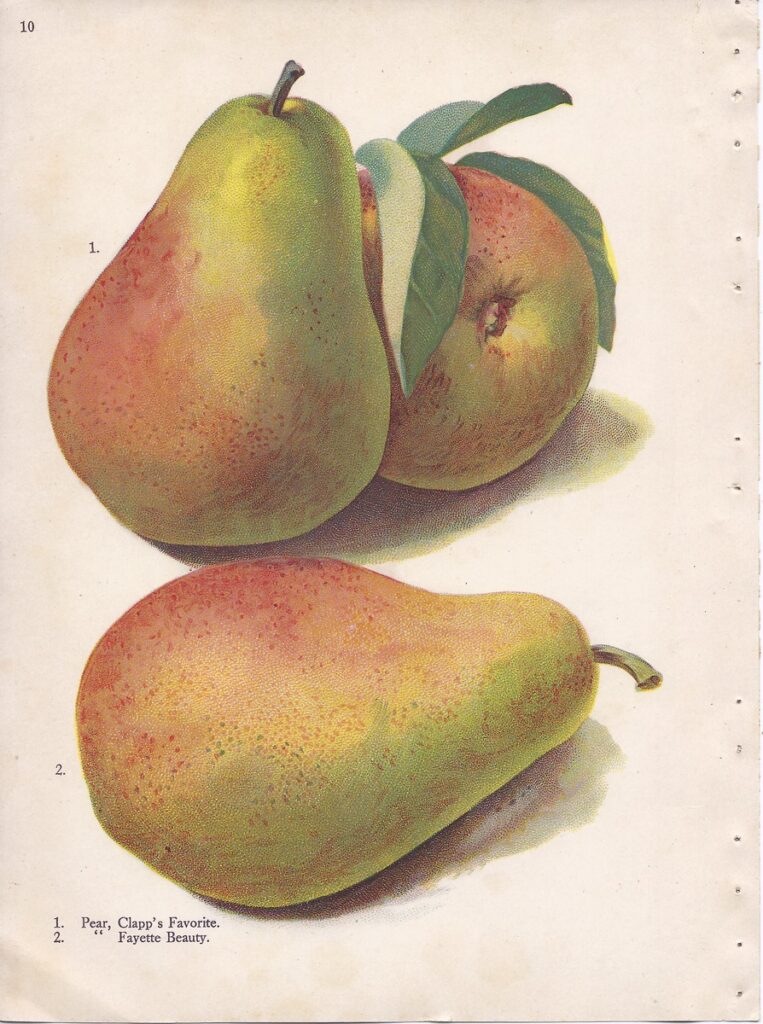

Clapp’s Favorite Pear

from Slow Food USA’s Ark of Taste

American Heirloom Pears

Pyrus communis

www.slowfoodusa.org/index.php/programs/ark_product_detail/american_heirloom_pears/

Reprinted from the Grapevine, Winter (December) 2012

https://airtable.com/shrC53HJPOIity774/tblUn1zYR4zdk2BGT

“Of the great pear country that once existed on Long Island, Boston back-county, Bucks County and Hudson Valley, perhaps not one thousandth still survives. It is a wonder that so many varieties of old American pears have survived to be grown at Corvallis, given the holocaust of American orchards.” —C. Todd Kennedy*

Clapp’s Favorite Pear is a large, oblong shaped orchard fruit. The thick skin is yellow with a red blush on its cheek, and the white succulent flesh is finely granular.

The Clapp family arrived during the Great Migration from Britain on the ship Mary and John. Prominent townsmen they acquired parcels of land stretching from the South Bay. The family founded and owned a grist mill that was pond-fed by the creek and tides of Bay.

Early in the 19th Century the family transitioned from general farming distributing to Boston’s marketplace to specialized wholesale production of fruits and vegetables. William Clapp had three son’s Thaddeus, Lemuel and Frederick who operated the farm. Thaddeus, a Harvard educated Scientist, bred and commercialized the Clapp’s Favorite Pear. The pear received acknowledgement by the Massachusetts Agricultural Club. In 1840, Clapp’s Favorite Pear was received as a local marvel and proofed to be commercially profitable. It was not only the finest pear but was thought at the time to have medicinal benefits.

A member of the Rosaceae family along with apples and peaches, this hardy, upright tree grows vigorously. The Clapp’s Favorite Pear flourishes in full sun and well drained loamy soil. It has white blossoms in the Spring. The tree sets fruit in 4-6 years and is available for harvesting 2 weeks before the Bartlett pear.

Clapp’s Favorite Pear is not an heirloom you will find in the supermarket. This early American variety must be harvested before ripe and has a very short life span. As the fruit ripens off the vine its best to eat or preserve right away.

Since they only last a few days upon harvesting, this is not a commercial variety that meets any of the criteria of modern food systems. You will find this variety at smaller, biodiverse Northeast orchards and offered in August at farmers markets.

Pear cuttings were brought from Europe to the American colonies. Pioneers used the fruit for eating and baking, the fine-grained wood for making furniture, and even the leaves to make a rich yellow dye. Perry, an alcoholic drink made from pears, was popular, but not as common as cider. Until pear growing was established on the West Coast, a good pear, imitating European standards, was a luxury of the leisure class and not a commonly disseminated fruit like the apple, peach, or cherry. Though treated royally in Europe, New World pears could not compete with America’s favorite fruit, the apple. Johnny Appleseed became part of our heritage, but the pear had no legendary counterpart, partly because pear trees grown from seed rarely produce usable fruit, but rather small rock-like fruits resembling wild pears. In addition, the pear tree preferred a milder climate and did not grow well in the climatic extremes of the East Coast, with its prolonged freezing and hot, humid temperatures.

By the mid-nineteenth century, the fireblight disease was introduced in North America, most likely from imported Asian ornamentals. This disease devastated East Coast orchards. The only pear not affected was the Kieffer pear, which is a hybrid of European and blight-resistant Asian species.

West Coast pears have their own unique history. They were originally brought by the Spanish to Mexico, Peru, and Chile, and traveled up the California coast with the early missions. Like the mild Mediterranean region, California has coastal valleys that are hot and dry in the summer and cold but not freezing in winter, perfect conditions for pears. The early mission settlers brought only what was essential, but that included pear budwood. They were carefully wrapped in wet straw or mud packs and packed in covered wagons or on the back of a mule to make the long journey up the California coast, where the budwood could be grafted onto quince.

The boom in California pear growing came after the Gold Rush, in the late 1800’s, when farmers planted large orchards of European pears to provide fruits for a growing population. Markets remained local and townfolk enjoyed fresh fruit up until World War II. After the war, the small, easily bruised heritage varieties were gradually eliminated in favor of a large pear that could be shipped, handled, and had a long shelf life: namely the Bartlett. The inland coastal valleys of California, Oregon, and Washington became the largest pear growing area in the United States, growing 90 percent of the pear crop, mostly Bartletts. In the 1950’s, the pear pack was destined for fruit cocktail and other syrupy can fillers, but today’s processed pears are more likely to end up as the base for a health juice, a flavored wine, or baby food.

Sources for pear materials, once abundant in this country, are rapidly disappearing. The great collections of varieties built up and maintained by pear fanciers have all but disappeared. Commercial growers who once took pride in growing many varieties of pears now confine their efforts to a few. Even experiment stations and universities find it difficult to maintain their variety collections because of pressure from other activities. What is true of the United States is also true of Europe and other regions abroad. France and Belgium, long considered repositories for pear materials, are rapidly reducing their variety collections for economic reasons. For these reasons, their preservation is of considerable importance.

Pear materials as known in the past will soon disappear unless the few remaining collections are preserved. It is true that the maintenance of these collections involves effort and expense but one can never adequately anticipate future needs. Materials that appear to be worthless now may ultimately become valuable as parent stocks in future pear improvement programs. Standards by which varieties are judged also change from time to time, and varieties now held in low esteem may conceivably become important in the future.

For a catalog of varieties and resources for trees and rootstock, listed by century of origin, visit the Slow Food website:: www.slowfoodusa.org/index.php/programs/ark_product_detail/american_heirloom_pears/

https://airtable.com/shrC53HJPOIity774/tblUn1zYR4zdk2BGT