Extracted from:

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Raspberry

The raspberry is the edible fruit of several plant species in the genus Rubus of the rose family, most of which are in the subgenus Idaeobatus.[1] The name also applies to these plants themselves. Raspberries are perennial with woody stems.[2] World production of raspberries in 2022 was 947,852 tonnes, led by Russia with 22% of the total. Raspberries are cultivated across northern Europe and North America and are consumed in various ways, including as whole fruit and in preserves, cakes, ice cream, and liqueurs.[3] Raspberries are a rich source of vitamin C, manganese, and dietary fiber.

Description

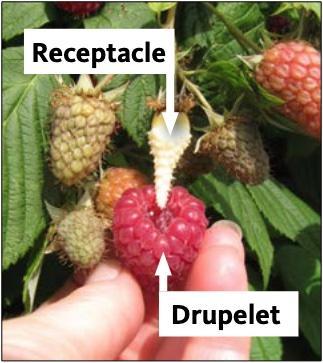

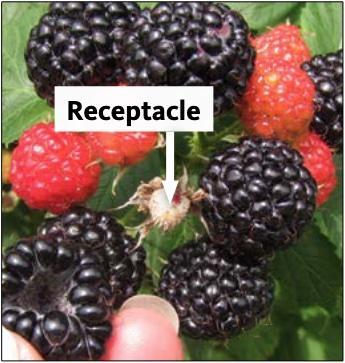

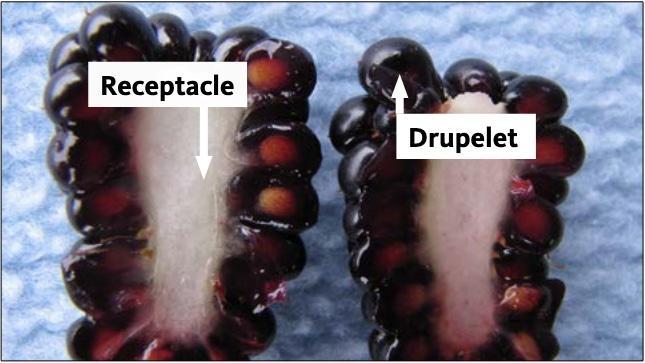

A raspberry is an aggregate fruit, developing from the numerous distinct carpels of a single flower.[4] What distinguishes the raspberry from its blackberry relatives is whether or not the torus (receptacle or stem) “picks with” (i.e., stays with) the fruit. When picking a blackberry fruit, the torus stays with the fruit. With a raspberry, the torus remains on the plant, leaving a hollow core in the raspberry fruit.[5]

Raspberries are grown for the fresh fruit market and for commercial processing into individually quick frozen (IQF) fruit, purée, juice, or dried fruit used in a variety of grocery products such as raspberry pie. Raspberries need ample sun and water for optimal development. Raspberries thrive in well-drained soil with a pH between 6 and 7 with ample organic matter to assist in retaining water.[6] While moisture is essential, wet and heavy soils or excess irrigation can bring on Phytophthora root rot, which is one of the most serious pest problems faced by the red raspberry. As a cultivated plant in moist, temperate regions, it is easy to grow and tends to spread unless pruned. Escaped raspberries frequently appear as garden weeds, spread by seeds found in bird droppings.

An individual raspberry weighs 3–5 g (0.11–0.18 oz) and is made up of around 100 drupelets,[7] each of which consists of a juicy pulp and a single central seed. A raspberry bush can yield several hundred berries a year.

_________________________________________________________________________________________________

Extracted from an article by Strik, B., Detweiler, A.J., Sanchez, N. and Dixon, E. 2021. Oregon State University Extension Service.

https://extension.oregonstate.edu/catalog/pub/ec-1306-growing-raspberries-your-home-garden

Oregon State University Extension Service

Growing Raspberries in Your Home Garden

Raspberries and blackberries can be distinguished by their fruit. Both produce a fruit made up of many individual sections, or drupelets (Figure 1A–C). Each drupelet encloses a seed. However, when raspberries are picked, the fruit comes off the receptacle — the white central core that stays on the plant — and the berry is hollow inside (Figure 1A–C). In blackberries, the receptacle stays attached to the fruit when you pick it — blackberries are not hollow.

Raspberries have a unique growth habit. The plants have a perennial root system and crown, or plant base. But the canes are biennial. Red raspberry plants have a lifespan of 10 to 15 years, while black raspberry plants live for five to 10 years, depending on the presence of pests or adverse environmental conditions.

Fruiting habits

Floricane-fruiting, or summer-bearing, raspberries produce vegetative canes, called primocanes, in the spring. Primocanes grow from buds on the crown and the roots (Figure 2). These primocanes grow throughout their first year and then go dormant in the fall. They overwinter and then produce flowers and fruit in their second year, at which point the canes are called floricanes. The floricanes die after fruiting. After the planting year, raspberry plants will have both types — primocanes and floricanes — at the same time (Figure 2).

Primocane-fruiting (fall-fruiting, or everbearing) raspberries have a similar cane development and life cycle, except the tips of the primocanes flower and fruit in the late summer or fall of their first year (Figure 3). The portion of the primocane that fruited dies back in late autumn or winter. Then the remaining cane base will overwinter and will fruit as a floricane in its second year, but will have a much lower yield than the summer-bearing types. The floricanes die after fruiting. Everbearing raspberry plants can be pruned to produce one crop (primocane only) or two crops (early summer on floricanes and late summer and autumn on new primocanes).

Summer-bearing raspberries produce fruit in June and July, depending on the cultivar and region. The fruiting season of everbearing raspberries is in June and July on the floricanes and from early August until the first frost on the primocanes, depending on the cultivar and region.

Raspberry cultivars

It is important to choose a cultivar adapted to your region. Various types of raspberry differ in fruiting season and cultural requirements. Even cultivars within the same type differ in fruit quality, flavor, appearance, tolerance to pests, cold hardiness and plant longevity.

You can find descriptions of newer cultivars online through various nurseries. Note susceptibility to disease, because this may limit planting life or production in your region. For example, cultivars susceptible to root rot are difficult to grow in most areas of the Willamette Valley.

Purple raspberries are not commonly grown in Oregon but may be a good addition to the home garden. They are excellent for processing into jams or pies. Choose a summer-bearing red raspberry cultivar if you want sufficient fruit during a more concentrated season for freezing or jam making. You may complement this with an everbearing cultivar for later season fresh fruit. It’s important to choose a cultivar adapted to your needs and site.

Because raspberry cultivars do not need cross-pollination to produce fruit, you only need to choose one cultivar. However, growing more than one type or cultivar will allow you to compare them, have sufficient fruit for freezing or jam, and to have fresh fruit for an extended period.

Table 1. Raspberry cultivars

Summer-bearing red or yellow raspberry – One crop per season on floricane

‘Cascade Delight’: Zones 6–9

‘Cascade Harvest’: Zones 6–9

‘Meeker’: Zones 5–8

‘Willamette’: Zones 5–8

‘Canby’: Zones 4–7

‘Boyne’: Zones 3–7

‘Encore’: Zones 4–7

‘Killarney’: Zones

‘AC Eden’: Zones 4–8

‘Prelude’: Zones 4–8

‘Cascade Gold’ (yellow): Zones 5–8

Everbearing red or yellow raspberry – Up to two crops per season

‘Vintage’: Zones 4–7

‘Heritage’: Zones 4–8

‘Caroline’: Zones 4–8

‘Joan J’: Zones 4–8

‘Polana’: Zones 3–8

‘Anne’ (yellow): Zones 4–7

‘Fall Gold’ (yellow): Zones 4–8

Photos: Bernadine Strik

Black or purple raspberry – Summer-bearing; one crop per season

‘Jewel’ (black): Zones 5–8

‘Brandywine’ (purple): Zones 4–8

‘Royalty’ (purple): Zones 4–8

Raspberry plantings are productive for five to 15 years, depending on berry type, soil and pest pressure. Carefully select a site best for optimal planting life. Ideal environmental conditions for raspberries are full sun exposure and fertile, well-drained, sandy loam or clay loam soils with moderate water-holding capacity. While plants can tolerate partial shade, yield and fruit quality may be lower. Raspberry plants are sensitive to wet or heavy soils and are susceptible to root rot (see “Common problems”). Raised beds or mounded rows, if constructed correctly, can create enough height for adequate drainage, if necessary (Figure 8). If possible, avoid spots in your yard exposed to high winds, which may make ripe fruit fall during fruiting or increase the risk of winter cold injury to primocanes.

Raspberries, especially blackcaps, are also susceptible to verticillium wilt, a soil-dwelling fungal disease (see “Common problems”). Avoid planting in sites where other verticillium-susceptible crops (such as strawberries, kiwifruits, potatoes, tomatoes, peppers or eggplant) and numerous ornamental trees, especially maples, have been planted in the past five years. Being aware of alternate hosts and changing crops will also disrupt other soilborne pest and disease cycles.

Table 2. Recommended soil nutrient ranges for raspberries

Phosphorus (P)

Bray 1 testing method: Deficient at less than 20–40 ppm

Olsen testing method: Deficient at less than 10 ppm

Potassium (K): Deficient at less than 150–350 ppm

Calcium (Ca): Deficient at less than 1,000 ppm

Magnesium (Mg): Deficient at less than 120 ppm

Boron (B): Deficient at less than 0.5–1.0 ppm

Soil pH

In the Willamette Valley and southwestern Oregon, a Shoemaker-McLean-Pratt, or SMP, buffer test is helpful for determining how much lime to apply if the soil pH is below the ideal range for raspberries. You can ask for this to be included on your soil nutrient analysis. In central, eastern and southeastern Oregon, soils tend to be neutral to more alkaline, so this additional buffer test is probably not necessary. Ideally, you would test the soil a year before you plant to give yourself enough time to modify the soil pH, if required.

If the soil pH is too high (above 6.5), acidify the soil with elemental sulfur. The application rate depends on soil type and the current pH of the soil. In sandy-type soils use approximately 1–3 pounds per 100 square feet; or in clayey-type soils use approximately 5–6 pounds per 100 square feet.

Drainage

Raspberries are sensitive to poor drainage. Because of their large root system, raspberries benefit when planted in well-drained soil that is at least 2 (and ideally 3) feet above the water table. Raspberry roots will suffocate in soils that are waterlogged for more than a few days in a row during the growing season, and the likelihood of root rot will increase. Gardeners in much of the state usually need raised beds either constructed of wood (Figure 8) or mounded soil (Figure 9) to ensure adequate drainage.

Nutrient management

Healthy raspberry plants with sufficient fertilizer nutrients have dark green leaves. Pale green or yellow leaves indicate a problem with nutrients, insects or disease. In particular, plants deficient in nitrogen will have older leaves that are paler green or yellow in comparison to younger leaves.

Your raspberry plants will need fertilizer in the planting and establishment years. There are many types of solid (granular) and liquid inorganic and organic fertilizers available. Most all-purpose garden fertilizers or organic products contain P (phosphate) and K (potash) as well as nitrogen (N), and some also contain Ca (feather meal, for example). Fertilizer sources range considerably in their nutrient content. For example, common inorganic fertilizers available for the home garden include 16–16–16 (16% each of N, phosphate, and potash), 20–20–20, and various slow-release sulfur-coated urea products. Organic sources include cattle (0.6–0.4–0.5) and horse (0.7–0.25–0.6) manure, yard-debris compost (1–0.2–0.6), cottonseed meal (6–7–2), feather meal (12–0–0), bone meal (2–15–0) and fish emulsion (3–1–1). Avoid using fresh manure products after planting; these may pose a food safety risk.

The main nutrient needed by raspberry plants after planting in all home garden soils is N.

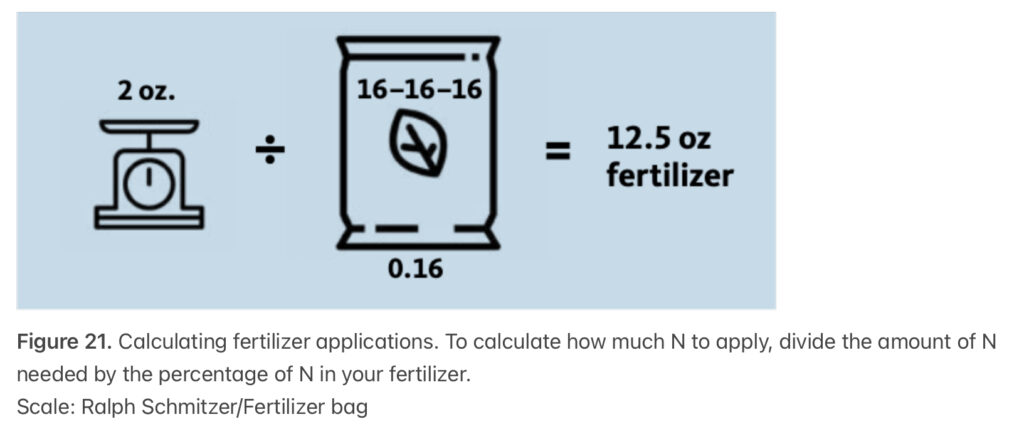

Fertilizer recommendations for N are given in weight of actual N per length of row for the year. How much fertilizer to apply depends on the percentage of N in the product. To calculate how much N to apply during the year, divide the amount of N you need by the percent soybean meal (6–2–1), you would need about 33 ounces, or 2.1 pounds of product (2 ounces ÷ ٠.06).

Summer-bearing and everbearing raspberries: 2–2.5 oz N per 10 feet of row

Black or purple raspberries: 0.5 oz N per plant

Table 3. Fertilization rates for new plantings in garden soil

Table 4. Fertilization rates for established plantings in garden soil

Divide into two applications

Summer-bearing red and yellow raspberries: 2–3 oz N per 10 feet of row per year

Everbearing raspberries: 3 oz N per 10 feet of row per year

Black or purple raspberries: 3 oz N per 10 feet of row per year

Established plantings

For each year after the planting year, fertilize summer-bearing red or yellow raspberries with a total of 2 to 3 ounces N per 10 feet of row per year. Fertilize everbearing raspberries with 3 ounces N per 10 feet of row per year. Fertilize black or purple raspberries with 3 ounces of N per 10 feet of row. Divide the fertilizer into two applications, applying the first in late March to early April (about the time when primocanes start to grow in the Willamette Valley).

Adjust the timing for other growing regions. Make the other application about 1½ to 2 months later (late May to early June in our example). Apply fertilizer more frequently on sandy soil, dividing the total rate into more split applications; apply organic sources of fertilizer earlier, as described above. Everbearing raspberries may require an additional 1 ounce per 10 feet of row in 1½ to 2 months (mid- to late July, for example) to ensure there is adequate N available for the later fruiting period.

Pruning black and purple raspberries

Black and purple raspberries will only produce fruit at the very top of a long cane under natural growing conditions. Pruning a primocane in summer during the growing season is called tipping. Tipping black and purple raspberry primocanes during the growing season increases yield four- to fivefold and makes the plants easier to manage.

Tip the primocanes in late spring or early summer by removing the top 3 to 6 inches (Figure 31A). Top them to a height of about 3 feet. You will need to go over the planting multiple times throughout early summer to catch all of the primocanes. The tipped primocanes will produce branches (Figure 31B).

Remove dying or dead floricanes any time from after fruit harvest through to late winter. Pruning in winter involves caning out the dead floricanes (Figure 32) (if you didn’t remove them in summer), and pruning the primocanes. In the Willamette Valley or southwestern Oregon, prune any time from December through February. In colder production regions such as central, eastern, and southeastern Oregon, prune as late as possible in winter to reduce the risk of winter cold injury and to remove any cold-damaged tissue (see “Common problems”). On the remaining primocanes, remove any damaged or diseased wood and use pruners to shorten the lateral branches on the primocanes to a length of 1.5 to 2.5 feet.

——————————————

For further information about weeds, pests, and diseases, refer to the original article. This article contains abundant information and references beyond that shown here.